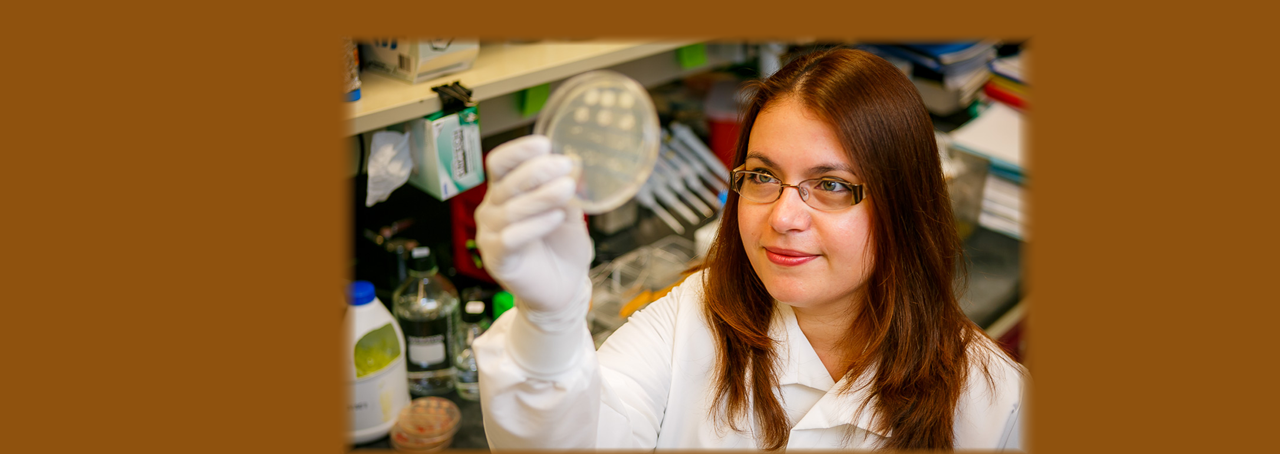

Passionate pursuit of answers

To understand Magdia De Jesus, first understand boxing. It's not about force; it's about grace. It's not about speed, but timing. It's not about reacting to the moment, but responding to the possibilities.

Boxing takes focus, commitment and far more creativity than the uninitiated suspect. It takes endless study.

And it helps to have a mentor.

Apply those skills to immunology, substitute a world-class research faculty for a former world champion featherweight and you can turn a Puerto Rican-born, Harlem-raised, self-confessed priss into a real scrapper in the lab.

“It was all about training really hard – as hard as you could – to see your growth,” said De Jesus, a research scientist and assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences, School of Public Health, University at Albany – Wadsworth Center.

What brought her to that sketchy underground gym in the South Bronx was as much curiosity as commitment. She just wanted to see what she was all about. “Here I am, an NYU student from Harlem who dressed all prissy,” De Jesus said.

It was enough to draw the attention of Juan LaPorte, a 40-win (22 by knockout) former Golden Glove champion. LaPorte ran De Jesus from workout station to workout station until she was ready for the ring.

LaPorte wasn't her first mentor – that would be fourth-grade teacher Victor Diaz – he wouldn't be her last. She's still collecting mentors, but counts Terry Krulwich, Luz Claudio at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Arturo Casadevall, now of Johns Hopkins University, and Nicholas Mantis of the Wadsworth Center among them.

“It's amazing how all the mentors imprinted a bit of themselves in my life,” De Jesus said.

“I think no one could really have done what she did without drive,” Mantis said. “She has an exuberance that goes past the bench.”

They encouraged her to pursue her passion – the basic questions. And for De Jesus, the basic questions involve the gastrointestinal tract. “I love the idea of how the intestine handles whatever we throw at it,” De Jesus said.

The intestines, are, in fact, a remarkably discerning gatekeeper into the human body. Think what they do: Whatever gets past your teeth, down your throat and through the pit of bubbling acid known as your stomach has to face the intestine. There, it gets profiled. And depending on what the intestines decide, the substance either gets absorbed into the blood stream or sent packing.

De Jesus has been mapping out that process, using confocal laser scanning microscopy and most recently Nanostring protocols to focus on three types of cell: B-cells, T-cells and dendritic cells. The Nantostring analytical tools discover which genes are expressed when the cells encounter a substance.

In short, the dendritic cells process the substance and create a profile of it, which is presented to the T-cells. The T-cells read that profile and secrete proteins called cytokines that activate the B-cells. If the substance is worth digesting – say, a warm caramel sundae with extra cherries – it gets absorbed and added to your waistline.

If, however, the dendritic cells find the substance is dangerous, perhaps a bacteria-laden, germ-infested bit of rotting french fry, the B-cells generate antibodies to protect the body.

“It starts a whole cascade of events that dictates how the intestine reacts,” De Jesus said.

Understanding how that process works – which genes are expressed and why – could be the focus of a long, full career. De Jesus has some shortcuts in mind. “Where it starts is with the development of the microparticle itself,” she said.

Inject the payload into a microparticle delivery vehicle made from baker’s yeast. (Seriously. Fleishmann's yeast, De Jesus said, giggling.) The yeast can survive the trip through the stomach to the intestine, where the microparticle can excite the process. “Why will it be tolerated? What happened? It goes on and on and on,” De Jesus said.

Give her two or three years. “We should have it all sorted out.”

Then what? De Jesus looks to answer basic questions, but those answers invite application. That focus is why the University at Albany and the Wadsworth Center support her work, but the National Institutes of Health has been a bit more critical, she said.

The applications? Imagine:

- Many vaccines can't survive the trip through the stomach acid; many of those that do get flagged by the T-cells are just tolerated and an immune response does not occur. What if those vaccines could be masked to create a gene expression the T-cells like and respond to positively? The result is oral vaccines that could be packaged in a syrup (maybe grape-flavored) so kids don't have to endure tears and sore arms when the annual well-child doctor's visit comes up.

- No cure exists for Irritable Bowel Syndrome, and many of the existing treatments have scary side effects: kidney and liver damage, increased risk of cancer, depressed immune system and the occasional brain infection. Understanding how the intestines malfunction to create the syndrome can lead to better treatments, even cures.

- Rotavirus vaccine, said Mantis, who has written several papers with De Jesus. “There may be a point in two or three years when someone could knock at her door,” he said.

“It's a strategy and you have to be able to ask the good question,” De Jesus said, and like a boxer planning a sequence of combinations, anticipate where the openings will be. “Now there's so much data we needed someone in bioinformatics to tease it out.”

“The question is what she could develop bench-side that's really a game changer,” Mantis said. “I could see it in a relatively short timeline, maybe five or 10 years.”

De Jesus' mentors helped her through the hard times, inspiring her curiosity and willingness to pursue a graduate education even though neither of her parents graduated from high school – although they valued education. They took interest in her work and pushed to questions she found both challenging and gratifying.

And they let her shine when strangers at the conferences were skeptical of either her sex or ethnicity. “I'm usually the only minority in the room,” De Jesus said. “I always have to demonstrate that I know my work and earned my position.”

That's OK. De Jesus is a scrapper; she'll respond with grace and timing and an awareness of the possibilities. “I have no problems being put through the ringer; I've grown up with that,” she said. “I actually enjoy showing them I know my science.

“That's the boxer in me.”

comments powered by Disqus